Elizabeth and Rosa

|

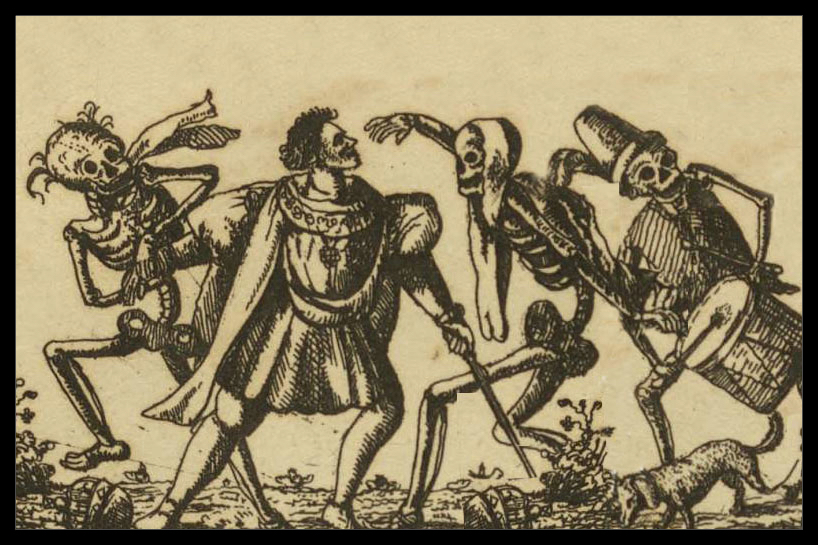

At 72, I am attempting to see and understand more clearly the life that I am living. I have been wrestling with this attempt to get all the pieces together into a somewhat understandable montage. If you are younger than I am and most people are, you might not be able to grasp my struggle. To be honest, I thought that I comprehended life pretty well as I started down my yellow brick road of life decades ago. Therefore, most of you might question my struggle. I would have if I were in your shoes as a younger person. In the past half dozen years, there have been three extremely transformative experiences: two dances with death and a trip to Myanmar (Burma). If those events have not happened to you, you will not understand my drive to address the brevity of life combined with human rights issues both here and abroad. My situation is an interesting paradox, because I am more driven than I was back in the days of the old civil rights movement during the 60s. It is an interesting conundrum; trust me. I feel more driven while having less time in which to address needed changes in social movements like racism. I came across a young woman, Elizabeth Jennings, who lived in New York City prior to the Civil War. On Sunday, July 16, 1854, she boarded a streetcar on her way to church where she was the organist.

The problem was that the streetcar conductor told her that blacks could not ride on segregated streetcars in New York. After a scuffle with the conductor and a police officer, Jennings was physically shoved off the streetcar landing in the street. This video clip is an old video of what streetcars looked like back then. Horace Greeley, who was a writer for the New York Tribune, wrote about this incident. Frederick Douglas also wrote about this incident. The result was that this racial occurrence became a big news story throughout the country. Jennings went to court and sued the Third Avenue Railroad Company of Brooklyn. She was represented by Chester A. Arthur, who became America's 21st president a quarter century after defending Jennings. Interestingly, Judge William Rockwell charged the jury prior to their deliberations, "Colored persons if sober, well behaved and free from disease, had the same rights as others and could neither be excluded by any rules of the Company, nor by force or violence." Even by 19th century standards, his charge to the jury was racist. Since Jennings was "sober, well behaved, and free from disease," she was awarded about $250 or a couple thousand dollars in today's money, and the streetcar company was ordered to desegregate their streetcars. What intrigued me about Jennings was that she was a young black woman. I immediately recalled this quote from George Eliot's novella, Silas Marner,

Eliot was correct; often a little child's hand leads us away from threatening destruction. Jennings was around 25 when she was kicked off the streetcar. Precisely a century later, Rosa Parks is on a bus in Birmingham, AL. After a Civil War and a century of dealing with racism, blacks could ride on public transportation but would have to give up their seat to a white rider. Parks learned from Jennings and refused to do so. Thus began the modern civil rights movement.

It is intriguing to me that the streetcar named desire drove both women to put their foot down and say, "Hell, no, I won't go quietly into the night."

Both riders on the streetcar named desire

Visit the On Seeing the Light page to read more about this topic.

Visit the Connecting the Dots page to read more about this topic.

Visit the The Last Lecture page to read more about this topic.

Visit the Dancing with Death page to read more about this topic.

"The Hand May Be a Little Child's" Visit the "The Hand May Be a Little Child's" page to read more about this topic.

Visit the Best and Worst of Times page to read more about this topic. 08/03/15 Follow @mountain_and_me |