|

Michelle: Turnabout is fair. You interviewed me; now, it is my turn to

interview you. I would like you to talk about your fall last spring

that nearly killed you. It has been just over a year ago. What has

the past year meant to you with all its struggles?

Al: The fall off the deck was an accident; I

was on a stepladder staining the side of the deck. Fortunately, for

me, Ann was working with me. However, I don’t recall anything that

happened. In fact, I don’t recall going to the hospital. I don’t

recall the three or four weeks in the intensive care unit at St. Mary’s

hospital in Hobart. I owe my life to my wife. If it hadn’t been

for her quick work of getting the paramedics there, I wouldn’t be

here. I feel that my life was spared.

The only downside to the fall is my hearing for

which I have two hearing aids. Outside of that, I’m taking no

medication now. I have had no seizures or no complications. The

neurosurgeon, Dr. Kaakaji, had to take out a round part of my

skull-plate from of my head. He did this to reduce the pressure of

the swelling, drain the blood, and whatever else he had to do. The

surgery was a couple hour procedure. I was without that part of my

skull that was the size of a bagel for months. After the first

month, the recovery was fairly quick. It is really interesting that

I always thought that someone would get better on a steady upward

curve. However, it wasn’t like that for me. I would get

a little better and remain like that for several weeks. Then I

would be much better one day. That would remain level for

several weeks, and again there would be another jump in improvement.

It just wasn’t a steady upward curve.

I appreciate Dr. Kaakaji greatly.

I told him when I went for a check-up that I am a Protestant whose

life was saved in a Catholic hospital by a Muslim doctor. The

world needs to get with this ecumenism.

Michelle: Like what kinds of improvement?

Michelle: Like what kinds of improvement?

Al: Wanting to do things. I wanted do things

like getting my life back together as far as exercising and things

like that. For the first couple of weeks at home, I would go for a

walk—one that would be about 100-feet, and I would come back. That

would continue for a couple weeks. Then all of a sudden, it would

just shoot up to the next level. Ann and I would walk all over the

neighborhood. Soon, I was walking around the lake.

The neurosurgeon told Ann that I had a 50/50

chance of making it through the surgery. I made it through the

surgery. The next issue was what I was going to be like after the

surgery. Several days after the surgery, Dr. Simaga came into the

hospital and asked me questions that I answered very well. However,

I don’t remember him being there, I don’t remember you being there,

or Ann being there. I don’t remember being in the hospital.

The neurosurgeon told Ann that I had a 50/50

chance of making it through the surgery. I made it through the

surgery. The next issue was what I was going to be like after the

surgery. Several days after the surgery, Dr. Simaga came into the

hospital and asked me questions that I answered very well. However,

I don’t remember him being there, I don’t remember you being there,

or Ann being there. I don’t remember being in the hospital.

An interesting thing was that Dr. Simaga, my

neurologist, told me when I went back to see him after the surgery

that he had asked me questions to find out how my brain was

functioning. He asked me one question about what was important in

my life. I said that I loved my wife and family, and I loved

teaching. Dr. Simaga told me that a couple of months later. It is

interesting even though I wasn’t sure why I was in the hospital; I

knew that there was an accident of some sort. However, while I

wasn’t clear about the accident, I was able to shoot back quickly

the answer to his question about what were the important things in

my life. While I don’t recall the entire hospital stay, I told

anyone who asked how I was doing that I loved my family and

teaching. For Dr. Simaga, that is pretty good, and it was a good

indication for him that there wasn’t anything permanently wrong with

me. I was going to get better, and I was going to be fine. He

wasn’t expecting such a clean-cut answer, but after brain surgery,

it was a good indication to him that I was on my way to a complete

recovery. His sharing that with me helped me jump to a new level of

recovery. That even though I was just out of surgery, I was still

thinking even though I don’t recall a nanosecond of the entire

hospitalization.

Michelle: What do you love about teaching?

Michelle: What do you love about teaching?

Al: I think that what I love about teaching

and what makes me a good teacher is that I take very seriously

teaching. Many professors are IQ-wise far superior to me. However,

I know my subject matter, and I love the process of teaching. What

makes me good was my childhood experiences in education. I grew up

in Pennsauken, NJ, which in that time, just after WWII, was an

average community with an average school system. I didn’t have any

problems academically. Nevertheless, my father had wanted to go to

college, but he wasn’t able to go because of the war. I was born

during the war, and my middle brother came soon after the war was

over. My father just wasn’t able to work fulltime and to afford two

young children, a wife, and go to college all at the same time.

However, it was his determination to make sure that he made college

available for all his children. He received a promotion at the

insurance company where he worked, but that opportunity forced him

to move from Pennsauken to Pittsburgh in the early 50s. He took

that opportunity, because it was a promotion. So we moved to Mt.

Lebanon, which was a southern suburb of Pittsburgh. Mt. Lebanon was

an extremely wealthy area well beyond our financial means, but he,

his wife, and his family struggled economically to live there.

Mt. Lebanon was at that time the 19th

best school system in the entire country. My father was more than

happy to live there so that his children would get a superlative

education in the Mt. Lebanon schools. What he didn’t realize was

that we had gone from an average school system to one of the very

best in the country. That educational jolt really knocked my socks

off academically along with my brother. We weren’t used to that

kind of excellence in education. I was in 5th grade when

we moved. I wasn’t prepared for what was expected of me. I was

able to get through school with Cs and Bs. I was not where I should

have been, and I wasn’t where all my friends were who had always

attended Mt. Lebanon schools. Many of my professors in high school

had doctorates. I didn’t think that I wasn’t smart, but I knew that

education wouldn’t come easy. Therefore, I played it safe...I didn’t

really try. I just wasn’t going to put a lot of effort into

something that seemed like a dead-end street to me.

Michelle: Why a dead-end street?

Michelle: Why a dead-end street?

Al: The idea was that in Mt. Lebanon everyone

was going to go to college. I was willing to go to college. I knew

that I wanted to go to school, but I wasn’t putting the effort into

it that most of the students I knew were putting in. Mt. Lebanon

was so far ahead of other schools back then. They were teaching

college level classes in high school, which isn’t uncommon now, but

back then, it was quite rare. Everyone that I knew was taking at

least one or two college level classes in their senior year of high

school. That was how Mt. Lebanon ran its high school. That was

just the mentality of the entire school system. They were offering

the best to the brightest kids around, but I was a kid from

Pennsauken who hadn’t spent his entire life there getting their

superlative education. I got there at the end of my 5th

grade. It was hard, and it taught me the wrong information about

who I was. I wasn’t like the other kids at Mt. Lebanon. The kids

with whom I went to school were children of CEO’s of big corporation

and other top-executives. So I was what I considered an average

student in what was a very wealthy and very educated elite school

system. After graduating from high school, I went to Muskingum

College. There I was a halfway decent student but still was getting

Cs and Bs and a handful of As. I went to graduate school in

Pittsburgh and did the same there also.

Michelle: Was it because you weren’t putting in the effort or did you just not

understand?

Al: I put in some effort to get by, but it

didn’t seem like it paid off. So I didn’t spend a lot of time

putting the effort in. Again, it seemed like a dead-end street to

me. I was so used to the reality that all the students that I knew

had parents who had been to college. Because of that, they were,

from my viewpoint, super students. There were some students that

would goof-off. However, all my friends were exceptional students.

I went through four years of college and three years of graduate

school with mostly Cs and Bs and the occasional A. Then I went to

my work-a-day life. Halfway through that life, I woke-up

academically and educationally to the need of a good education and

more education. So went back to get my doctorate. By then, I had

realized that I needed more education. It woke me up, and I

graduated at the top of my class with honors.

Michelle: What

made you realize you needed more education?

Al: Because I wanted to succeed at a higher

level. I wanted more job opportunities. And I knew that the only

way to do that is to prove to yourself educationally. So I went and

got my doctorate. That coming of age took me almost twenty years to

wake-up. When I woke-up, I realized that I wasn’t dumb, I wasn’t

lazy, and I understood why I had suffered and stalemated much of my

education in high school, in college, and in graduate school.

Another thing, for which I am very grateful,

was a college professor who really gave me an opportunity to do well

in education. His name was Louie Palmer. He taught, what was called

back at Muskingum, The Arts. It was an art history class of five

hours for two semesters. Those ten hours in my junior year planted

the seeds for me and teaching. I did well in that class—well enough

that he asked me to help him teach subsections the following year.

I became his teaching assistant. Students would attend three large

lectures weekly and then have two smaller subsections. So I would

teach a half-dozen subsections a week. In fact, for that year when

I was a senior, I wrote all the midterms and the finals and taught

the subsections. That had a profound effect upon me. I was

teaching students who were contemporaries of mine. It was a hoot.

It was also the first time a professor ever said to me, "You know,

you are really good at teaching." He gave me the opportunity to

teach without any testing of me to find out if I could do it or

not. In fact, it still intrigues me that he would trust me that

much. He must have seen something. I was a homecoming committee

chairperson, I taught, and those were probably the best two things I

did in college.

Another thing, for which I am very grateful,

was a college professor who really gave me an opportunity to do well

in education. His name was Louie Palmer. He taught, what was called

back at Muskingum, The Arts. It was an art history class of five

hours for two semesters. Those ten hours in my junior year planted

the seeds for me and teaching. I did well in that class—well enough

that he asked me to help him teach subsections the following year.

I became his teaching assistant. Students would attend three large

lectures weekly and then have two smaller subsections. So I would

teach a half-dozen subsections a week. In fact, for that year when

I was a senior, I wrote all the midterms and the finals and taught

the subsections. That had a profound effect upon me. I was

teaching students who were contemporaries of mine. It was a hoot.

It was also the first time a professor ever said to me, "You know,

you are really good at teaching." He gave me the opportunity to

teach without any testing of me to find out if I could do it or

not. In fact, it still intrigues me that he would trust me that

much. He must have seen something. I was a homecoming committee

chairperson, I taught, and those were probably the best two things I

did in college.

Michelle: Because of how it made you feel?

Al: Yes, it was really the first time that I

really felt good about education. It started to give me that kind

of feeling that all my friends had back at Mt. Lebanon, and that I

had missed for the years prior to that teaching experience. So I

love teaching and taught The Arts for a whole year. I can’t

remember what I was paid back in those days. It was a several

hundred dollars a semester, which was good money back then.

However, I would have done it for free. It was the most valuable

lesson that I ever learned. I owe Louie so much. He took classes

to Florence, Italy between semesters. I used to babysit for his dog

and live in his house when he was away. Louie changed my life.

After I got out of graduate school, I went to Scotland and took a

year of graduate study there, but there was also another reason to

go overseas. I wanted to see and visit in person what I had learned

and then about which I had taught in The Arts. I went to school at

New College in Edinburgh, Scotland for a year. In the summer before

and the summer after, I went through all Western Europe and parts of

Central Europe in large part to see firsthand the buildings,

paintings, and sculptures, which I knew so well from The Arts. It

was a great experience for me, and I owe Louie a great deal of

thanks for helping me on my way.

So what I learned about myself and about

education is critical for the way I view teaching. Not everybody in

my classes are going to be straight A students. Some of them are

working and many of them are as I was before I turned my educational

life around. That is the great thing about teaching; you have an

opportunity to turn students onto learning students. I guess that I have

become a Louie Palmer to another generation of students. You have

the opportunity to save somebody from wasting away twenty years of

his or her life.

So what I learned about myself and about

education is critical for the way I view teaching. Not everybody in

my classes are going to be straight A students. Some of them are

working and many of them are as I was before I turned my educational

life around. That is the great thing about teaching; you have an

opportunity to turn students onto learning students. I guess that I have

become a Louie Palmer to another generation of students. You have

the opportunity to save somebody from wasting away twenty years of

his or her life.

Michelle: So

how do you think you can do that, or how do you do that?

Al: Many times, I tell them the story that

about my educational history. I’ll often begin my classes telling

that story when I introduce myself. I say to them that I graduated

at the top of my class when I was getting my doctorate. Then I ask

if they are impressed. They honestly are somewhat surprised and

delighted. Then I add that it is interesting, because, when I was

getting my bachelors and my masters, I was getting Cs and Bs and

couple As. The thing that motivates me about teaching is that I

don’t want other students to have to go through wasting 20-years by

hitting their heads against a brick wall. That desire of mine will

keep me teaching forever. I woke up, and I don’t want other

students to have to wake up midway through their lives. So I give

them an opportunity. I tell them what they have to do in class.

Here is the syllabus, here is the grading system, here is what you

are expected to do, and here are the threaded discussions online.

Now, you are either going to be following my instructions or you

won’t. However, you have a choice, but if you don’t follow my

instructions, you will waste 20-years of your life as I did. That

does wake-up some students.

Michelle: What specifically do you want them to take away from your class?

Al: I tell them there are two grades that they

are going to get for their class. The one that goes to the

registrar that I don’t care about at all. I tell them that five

years from now, you will forget the grade you got, and in ten years

from now, you will forget the class. However, the grade that I care

you get will make all the difference in your life and work. I want

them to take from this class lessons that will make a difference in

both their professional and personal lives. I want them to take

away something that will help them change, motivate, and strategize

in your workplace or home.

For example, I teach an art history class.

How’s that for a surprise? In the class, they have to write a

twelve-page paper about an artist of their choice. However, all art

comes out of some sort of pain. Pain generates creativity.

Therefore, they will pick an artist of their choice and find out

what that pain was that motivated that person in the arts. The

paper can’t merely be about some artist, but it does have to deal

with the artist’s pain. They will learn about the artist and his or

her pain. There are two lessons there. One, the artist overcame

some sort of pain while making the artist great. Two, the pain and

the resultant drive to deal with the suffering is a good lesson for

each student. Don’t avoid pain...deal with it. You can’t name an

artist that doesn’t have some kind of pain/suffering/personal

problem, etc. It is true that there is no such thing as a great

artist that hasn’t dealt with a great deal of pain. Whether it is

family pain, drugs/alcohol, physical pain, psychological issues,

racism, sexism or even educational pain, that pain drove them to

greatness. What I want my students to take from the paper is a lesson

about their own lives. I want them to vicariously live and learn

about where greatness comes. Pain, if dealt with creatively, is a

good thing. It is the thing that will help motivate them to go on

beyond the pain and push them to greatness also. It doesn’t matter

whether a student is right or left-brain. They can use that pain to

ask, "How I can gain from my pain?"

I teach a 20th and 21st

century history class. We deal with great leaders of the world.

They don’t have to be artists to be great, but they all have dealt

with pain well. That is what dealing with pain does for the

person. If you don’t have the pain and creativity, you won’t be a

good leader. Winston Churchill became a great WWII leader, but he

came out of a painful situation of screwing up in WWI. In every

pain, there is going to be gain if you look for it and seize it.

What I want my students to learn is a critical lesson of life.

I teach a 20th and 21st

century history class. We deal with great leaders of the world.

They don’t have to be artists to be great, but they all have dealt

with pain well. That is what dealing with pain does for the

person. If you don’t have the pain and creativity, you won’t be a

good leader. Winston Churchill became a great WWII leader, but he

came out of a painful situation of screwing up in WWI. In every

pain, there is going to be gain if you look for it and seize it.

What I want my students to learn is a critical lesson of life.

I teach a sociology class, and, there again, I

want them to do their term paper about some pain that they have and

how the sociologist deal with these kinds of issues. I have many

students that are female and/or a minority. They don’t have to look

for pain very far; they already are experiencing it due to sexism

and/or racism.

My class has now to figure out what various

sociologists are doing to resolve those types of problems or pains,

which could include sexism and racism. They are given a golden

opportunity to learn in the classroom something that pertains to

their real world. If they do what is expected, they will get an A

or B. However, the grade that is most important will be given to

them out in the world. What I really want them to do is to learn a

problem-solving strategy. They can take what they learn in the

class and apply it to their real world. Instead of merely

complaining and suffering, deal with the issue. Research what

others suggest. However, I want them to be proactive. Address the

problem and deal with it. Many of these classes are taken because

they are required courses to graduate. From me, they are learning

to deal their problems head on and not merely to avoid them. If

they learn that lesson, they will be building the foundation for

their greatness. And I think that is real teaching.

Michelle: Do you have any antic dotes about any particular students that really

got it?

Michelle: Do you have any antic dotes about any particular students that really

got it?

Al: I was teaching a psych class sometime ago,

and the class was taking a midterm. I was walking around the room

keeping an eye on the students while they took the test. I passed a

guy who hadn’t written anything on his test paper. I came back

fifteen minutes later, and he still hadn’t answered a single

question. I said to him

that we only have a little time left, and he had better get

going and start writing. At the end of the class, he gave me

his test, and he had written something down. He had written the date

next to his name. I asked him what had happened. He replied that

he was from Gary, IN. I said, "You forget that I’m from Crown

Point, IN, so what? He said that he never learned how to study. I

asked whether he had read the chapters of the book from which I had

written the midterm questions? He said that he had, and he showed

me his book. He had highlighted every word in the first half

of the book. I asked where he had learned that skill. He said he had never

learned it; he just figured that was the way to learn.

I helped him the rest of the semester. He

wound bringing up his F to a B-. That was remarkable. He turned

his life around. The kid just happened to be another Al Campbell.

He came from inner city school that really didn’t teach very much,

but he had the brains. However, he didn’t have the guts and the

understanding that he needed. Once he was given a little bit of

help, the kid accelerated.

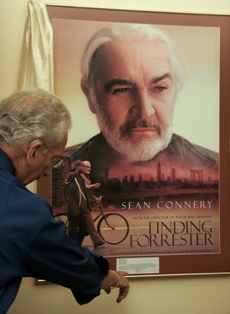

During that semester, Ann and I happened to be

going to a movie that I really didn’t know much about it other than

Sean Connery was in it. It was called Finding Forrester. We

weren’t into the movie very long before Ann nudged me and said,

"That is you and your student; isn’t it? You are Forrester, and he

is Jamal." I told the student to see the movie when I saw him the

next time. In the meantime, I had asked a friend who managed a

theater to give me the poster of the movie. I was going to frame it

and put it in my office. The following week I get a note in the

mail. It was that student. He started his thank-you note by

writing, "Dear Forrester". He wrote a nice note and signed it

"Jamal". I had the note framed at the bottom of the movie poster.

During that semester, Ann and I happened to be

going to a movie that I really didn’t know much about it other than

Sean Connery was in it. It was called Finding Forrester. We

weren’t into the movie very long before Ann nudged me and said,

"That is you and your student; isn’t it? You are Forrester, and he

is Jamal." I told the student to see the movie when I saw him the

next time. In the meantime, I had asked a friend who managed a

theater to give me the poster of the movie. I was going to frame it

and put it in my office. The following week I get a note in the

mail. It was that student. He started his thank-you note by

writing, "Dear Forrester". He wrote a nice note and signed it

"Jamal". I had the note framed at the bottom of the movie poster.

I have all my students see that movie or The

Emperor’s Club. Both of them were about teaching situations

with students—some who get it and some who don’t. All my students

have to write a two-page paper, for which they get no credit, but I

tell them that if they don’t get the paper in that I will forget to

enter their course grade with the registrar. The title of their

paper is "Why in the Hell Does Campbell Want Me to See This Film?"

Both those films raise important questions about teaching,

education, and the student.

Michelle: What frustrates you about teaching?

Michelle: What frustrates you about teaching?

Al: I think that it is my failure to wake-up

everybody. If you look at my student evaluations, they are

generally exceptional. However, since they are so exceptional, I

believe that I am good at teaching. I don’t understand why I can’t

wake-up everyone. I have a story; it is not that I am the golden

child of education. It is just that I have learned an important

lesson about teaching—an important lesson about the learning

process. I feel that I have failed students if they don’t wake-up

now and shortcut wasting their lives. That frustrates me. It

frustrates me when students plagiarize. Plagiarism is a theme that

runs through both movies. When I was in high school, college, and

graduate school, I was smart enough to know not to cheat. I knew

that we couldn’t write as well as any of the textbooks. However,

nowadays, some students think that they can. When the paper is

written better than I could write it, it is a sign of cheating.

That frustrates me, because the student is learning the wrong lesson

when he or she plagiarizes a paper. That is a bad lesson that they

learn, and they will take it with them into the world.

Michelle: What

specifically bothers you about it? Is it that they are not putting

forth the effort or lying about it?

Al: Both. In addition, I have told them not

to do it, and it is not going to help them. It is going to be

detrimental to them in life beyond the ivy-covered walls of school.

I am serious about that. I can understand why some students are

tempted to cheat, but it will hurt them both while in school and

when they get out into the world. I went to school; I have nearly

300-hour of post high school education behind me. Three-fourths of

the professors, which I had, might have been smart people but

weren’t teaching very well. At least, they weren’t concerned about

the student both while in school and when the student is in the

workplace. The vast majority of my students do not cheat, but two

or three students each term will plagiarize. That just drives me

nuts. I haven’t gotten through to them. It is not going to help

them academically or in life in general.

Michelle: You mentioned that you were different from other professors in what way

exactly?

Michelle: You mentioned that you were different from other professors in what way

exactly?

Al: I think that some professors are really

good at what they know but can’t express it well. I think other

professors teach, because they didn’t know what else to do. I think

some professors teach because the pain of something. It goes back

to the great artists’ pain. Some people didn’t have much pain.

They just coasted through, gotten their degrees, found some job, and

taught until they retired.

Michelle: They

haven’t woken-up yet?

Al: No, they haven’t woken up at all. The

pain wasn’t great enough to wake-up.

Michelle:

How many years have you been teaching now?

Al:

Twenty years. I have taught at Purdue North Central, St. Francis,

DeVry, and Moraine Valley.

Michelle: Do

you think your teaching has changed at all over those years. Or has

your focus or drive changed?

Al: I think that I am much more in my

students’ faces about issues and see it as much more important for

them. Each year, it becomes more important that they get it and is

much more of a verbal thing for me.

Michelle: Why

does it become more important?

Al: Probably my age. I know that I have x

number more years to teach and actually live. I have to teach

and I am going to make every effort to be the best that I can be. The

students that I have helped wake-up have motivated me more and

more. It is a win/win situation. I see students that I have helped

in some way, and it is a hoot to see them and know that I helped

them. I hope that my students will remember me as their Louie

Palmer.

Michelle: Do

you think your attitude or anything about your teaching has changed

because of your fall?

Al: I don’t think it has necessarily changed

anything because of my fall. I am in an economic situation where I

could be fairly forceful about wanting to teach and wanting to help

students.

Michelle: You

feel that just has to do with economic reasons.

Al: I think that one of the things that the

fall did for me is to skate me close to death. While avoided it, in

2008, one of the things that I have learned was how close I came to

dying. And yet, I didn’t, but that has rattled my brain.

Michelle: Physically and ahhh?

Michelle: Physically and ahhh?

Al: Physically and emotionally. It has made

me think about death. At your age, you understand death, but you

don’t truly understand it. You can’t feel it. Prior to my fall, I

understood death, but I didn’t really feel it. It wasn’t something

that was a reality to me. While I skated through my first death

experience, it has given me kind of an eye-opening experience about

life and its brevity. It also supplied me with the importance of

doing things in life that you want to do. I don’t fear death

anymore.

It gave me the freedom to skate a little wider,

a little faster, and a little different than I would have had I not

brushed so close to death. Many people at my age wouldn’t even be

thinking or worrying about death. I don’t want to die, but I’m not

going to fear it. My near-death experience gave me a kind of carte

blanche to do what I need to do. I need to teach as much as I can.

One of my deans, Anne Perry, last term called and said that she had

four classes, and she had to find professors to teach them. I asked

her which classes did she need a professor. She told me, and my

response was that I would take all of them. Anne said that she knew that I

would say that, she hung up, and all was well. So my fall taught me

an important lesson of life—we aren’t going to be here forever.

That is also why I travel so much around the world.

Michelle: How

much longer do you think you will teach?

Al: I’m teaching now about three times the

number of hours a normal professor teaches. So I spend all my

waking hours doing housekeeping, ironing, cooking.... Just kidding.

However, I spend a great amount of time either in the classroom or

in front of my computer teaching online. I will do that for the

rest of my life. Teaching is like being a parent. It goes back to

what I said about teaching and loving my family. It is the same

kind of thing; how long am I going to be your parent? There is

always going to be something I can offer to my children and/or

students. When am I going to quit being your parent? If I maintain

my health, I will teach as long as they will have me. We have

enough money to quit teaching right now. Retiring would resolve

issues like plagiarism, but what would I do? We could go travel and

I could learn more things so I could take them back to where? I

love taking pictures of places we have been and have them blown up

for the walls in our home, but there is a limit to the total

number—and we are nearly at that limit now. I am going to go out and

learn, so I can share that with other people.

Michelle: Is

that what you like most about traveling?

Al: Well, I like to see and experience some

place new with Ann. I like to see something we hadn’t seen before.

I love the excitement and the opportunity to learn the history of

the people and that kind of thing. I love to see things for the

first time; I love to go to places where most other people don’t

go. Ann and I have this little deal between us. It is called "good

trip/bad trip". The bad trips are the ones I really

love. Ann likes the good trips like to Bora Bora and Easter

Island. I like the bad ones that are difficult trips—like our trip

to India, Tibet, Nepal, China, and Mali. The trip to Africa in many ways was

quite difficult.

Michelle: What was difficult about it?

Michelle: What was difficult about it?

Al: We don’t go on tours; we do it ourselves.

I wanted to go to Timbuktu out in the middle of nowhere in Mali.

The only way to get to Timbuktu was to bounce your head against the

top of an SUV for hours and hours and hours. But, finally, you get

there. You don’t know many people that can say that they have been to

Timbuktu and Katmandu. Katmandu was same kind of thing except for

it was in Nepal. You can’t imagine, well, you can since you were in

Africa for a year, what you learn from those experiences. I have

taught a class in Tibet and China. I’ve been to Tibet twice along

with India and Nepal. We have traveled in the South Pacific and

have been to Chile and Easter Island. I have been all over Europe

and most of central Europe. I have been in the Middle East. All

traveling is fun and a learning experience. Some trips are just

easier than others are. In several months, Ann and I will be going

to Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand in December and January.

You have no idea how much you bring back for the classroom.

Michelle: In what way?

Al: We were talking about my teaching a world

religion class. We were covering some issues in some African religions.

One item, which drives students up the wall, is circumcision that is

still performed on some children--males and females that are ten to

twelve years old. The students got into arguing about circumcision

and whether it was still done. I showed them pictures in Dogon

Country where it is still done to both boys and girls prior to them

becoming teenagers without antiseptics. Dogon Country was on the way to Timbuktu. This

is the place where the locals hid out when the Muslims came through

North Africa over a millennium ago. The locals fled into the hills

and hid from the Muslim invasion. Over the centuries, the locals

filtered down from the mountains and mixed with the Muslims. Now,

Dogon Country is completely a Muslim dominated area. I could bring

to the discussion what the locals in Dogon Country thought and said

about circumcision of both sexes. Having been there, you bring to

the classroom an inordinate amount of information about what isn’t

in the textbook.

In the art history classes that I teach, I

spend so much time talking about what never shows up in the

textbook. There is the debate about the lost continent of Atlantis

in both the philosophy of Plato, history, and in the arts. Many believe that

Plato was talking about the Greek island of Santorini also called

Thera. The liberal arts classes can easily be interrelated. There is

an amazing amount of information out there that students float

passed when reading a textbook.

In the art history classes that I teach, I

spend so much time talking about what never shows up in the

textbook. There is the debate about the lost continent of Atlantis

in both the philosophy of Plato, history, and in the arts. Many believe that

Plato was talking about the Greek island of Santorini also called

Thera. The liberal arts classes can easily be interrelated. There is

an amazing amount of information out there that students float

passed when reading a textbook.

Another example, I came back from Tibet and

China after teaching there. I was there for about a month, and it

took me another month to get over congestion and not feeling

well—just because of air pollution in China. The Chinese are willing to try

to stay up with the world in the 21st century but are

going to kill their people in the process due to bad health. They

have indigenous people sweeping the streets clean, but the air

everyone breathes is grossly polluted. So it is that contradiction of

reality that is China. I was teaching a history class, and I told

my class about driving on what would be considered an interstate in

China. Miles from the city and the population, there was someone

there dusting the top of the guardrail on the side of an overpass.

Miles away from the city, someone was dusting the overpasses. She

was doing that for aesthetics while everyone was breathing polluted

air from cars and trucks without proper emissions controls. The

textbook never talked about that dichotomy. Traveling adds a vast

amount of information for any of my classes. I tell them also that

to get a really good education, they will have to travel beyond our

borders. Take one trip to one place that you feel comfortable,

because they speak the same language. Once you get two weeks over

there, then traveling and learning will be contagious. Besides,

there are very few places in the world where we have been where they

don’t speak English as a second language.

We were in Egypt were someone told us that they

like everything about the Americans but the government and the Bush

administration. I replied that he should wait until the next

election.

We were in Egypt were someone told us that they

like everything about the Americans but the government and the Bush

administration. I replied that he should wait until the next

election.

We went to French Polynesian in part to visit

Tahiti. The primary reason I wanted to see Tahiti was because that

is where the artist, Paul Gauguin, went when he broke off his

relationship with Vincent van Gogh. I wanted to see those people

that he said were beautiful people. When we got there, we

discovered that Gauguin was right. The French Polynesians were

all beautiful people. They are lovely people, and they have

nothing. There isn’t a person in the United States that is as poor

as the average French Polynesian. We went past their homes that

they lived in—four walls and open windows and one or two chairs.

Nevertheless, they were beautiful people. I have never seen people

prettier in my whole life. In addition, they are loving and gentle

people. That is why Gauguin stayed there for such a long time.

They were indeed, lovely, lovely people. People who don’t go

overseas are wasting precious time. Sooner or later, they won’t be

able to travel, and then they die—having wasted the gift of life

that they could have truly experienced.

Michelle:

Speaking about education, what about your job offer to teach

fulltime at St. Francis?

Al: They offered me the job that would have

started in August, but then I fell in May. They weren’t sure how

long my recovery would be so they offered the job to the next

person. However, I was fine, because I was back teaching as an

adjunct in August. Nevertheless, what is more important is how I

handled the loss of the job. I would have preferred to learn some

other lesson of life. However, it goes back to art history and how artists

become great because of some sort of pain. I haven’t changed my teaching style, my attitude toward

students, and I will never quit teaching. I’m still teaching three

times what a normal professor would teach...and I still love it.

Michelle: What is next for Al Campbell?

Michelle: What is next for Al Campbell?

Al: I would like to teach overseas. I was

looking at a job in Kurdistan in northern Iraq, but Ann said that

there weren’t enough beaches there.

It would be nice to teach

American students overseas or local students who want to learn. I

would also like to interview Obama, but he is going to do well

without my help. I don’t know, but I don’t see myself as retiring

and sitting down at the dock fishing. However, I would like to

teach at an overseas university somewhere.

Michelle: 2008

was an interesting year for you as far as medical issues.

Al: 2008 was not a good year for me as far as

my health was concerned. I started off the year with prostate

cancer. One of my best friends died of prostate cancer half-dozen

years ago. I went to see him at the University of Chicago

Hospital. It was too late for him to have surgery. Because of that

and the fact that all males will get prostate cancer if they live

long enough, I was pretty conscientious about getting a PSA test

annually. My PSA was elevated in 2007, and I went to the University

of Chicago Hospital for a prostate biopsy, which showed cancer. I

had prostate surgery done robotically with the da Vinci surgery

procedure. Dr. Zorn, the surgeon, never touched me with his hands.

He just used robotic controls to operate, and I have a few small

incisions, but I had the surgery in January of '08. It was a snap,

and I was home the next day. I have gone back to my normal life

without any problems or complications.

Michelle: Did it affect you emotionally at all?

Michelle: Did it affect you emotionally at all?

Al: No, the robotic thing saves a lot of

tearing and doesn’t cause any dysfunction. If anybody reads this

and is thinking about prostate surgery, go to the University of

Chicago Hospital and ask for Dr. Zorn. Don’t let anyone else touch

you. Dr. Zorn is a great, young surgeon. He is just a sharp

character. The surgery and the after-effects were a snap.

Then a couple months later, I fell off the

ladder and that was no snap. I have always had problems with

breathing, which has nothing to do with the fall. However, I had

gotten to the point where I was tired of problems and wanted to be

proactive. Again, it was one of those times where I was floating

along for a while, and then you jump up to an all-new level. I got

to the point where I put my foot down and got my ass in gear. I

went in to see Dr. Simaga, my neurologist, and told him about my

breathing problem. He said to go Dr. Covello in Munster. Dr.

Covello saw my records, looked at my nose, did some tests, and then

he told me what he’d do. Again, it was a nice clean surgery, and I

haven’t breathed so well all my adult life. Again, if you have a

problem with breathing, call Dr. Covello.

Then I had some leg muscle problems, not spasms

just twitches, for a couple weeks. This was something related to my

fall. It was a neurological problem that I wanted resolved. So I

went to two tests that were separated by several weeks. By the time

that I got the second in-depth test, the problem was going away.

Now, I hardly recall it. 2008 was not a great year medically, but

it could have been a lot worse. I could have been dying of prostate

cancer, or I could have died from the fall. So it wasn’t that

bad...right?

Dr. Simaga had asked Ann how I was dealing with

the aftermath of the fall. She said, "Oh, he gotten back to his

normal, crazy self like he was before the fall." I took that as a

compliment. I’m not sure whether Dr. Simaga he did or not.

Again, if you have any neurological problems, see him.

Michelle: Again, what is next for Al Campbell?

Al: One of the things in the history class

that comes up and one thing about which I feel very strongly about

is Aung San Suu Kyi. Ann and I have a little argument occasionally

about my desire to interview her. She's afraid that the Myanmar

government might kill me if I attempt to do so. That isn’t much of a concern. Since my

fall last year, I don’t fear of death. However, the fall hasn’t

quelled my fear of torture. Having said that, there is no one that

I want most to interview...other than Aung San Suu Kyi. Looks like I

will settle for Barack Obama...at least for now.

Michelle: Why

would you like to interview Aung San Suu Kyi?

Al: Because she is like the daughter of George

Washington to the Burmese. She has guts and determination, but she

is pleasant without being aggressive. She is a woman who is in her

own league and isn’t afraid to live that way. It would be an honor

for me to sit down with her for a couple hours of conversation.

Just a couple weeks ago, some Westerner tried to get into her place

where she is under house arrest. I would love to interview Aung San

Suu Kyi. Again, it would great for my teaching of a 20th

and 21st century history course. Most of my students

don’t know who she is, yet she is a woman that has intimated the

communists in Burma. All Westerners need to know who Aung San Suu

Kyi is. She won a Nobel Prize for Peace in 1991. However, like I

just said, it looks like Barack Obama’s interview will be easier to

obtain.

6/09

|