Answers from Vonnegut and Faulkner

When I was a small child, not even in elementary school, the family would pack up for a week or two to go down to shore. Down to the shore is a term that people in New Jersey use when they talk about going on vacation. During the summer, people flock to three dozen or more towns scattered along the New Jersey coast. Growing up in New Jersey allowed my family to enjoy places like Beach Haven, Atlantic City, Ocean City, and Cape May.

When I grew up and had my family, we often retraced places I had been when I was their age. In the early 70s, we went to Ocean City with my family and Ginger, my first Irish Setter. We would go for walks on the boardwalk, visit an amusement park, and spend much of the day on the beach. While the children played, I spent hours reading Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five.

The full title is Slaughterhouse-Five, or, The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death. The novel is about Billy Pilgrim, a POW, during WWII. The British and Americans were bombing Dresden, which leveled the entire city.

Billy, along with other POWs, was in a slaughterhouse that the Germans had converted into a prison.

While reading about space aliens capturing Billy Pilgrim, my mind floated between reading Slaughterhouse-Five. While the sun beat down upon me, I often was unsure where I was.

The quasi-autobiography Slaughterhouse-Five was also made into a film.

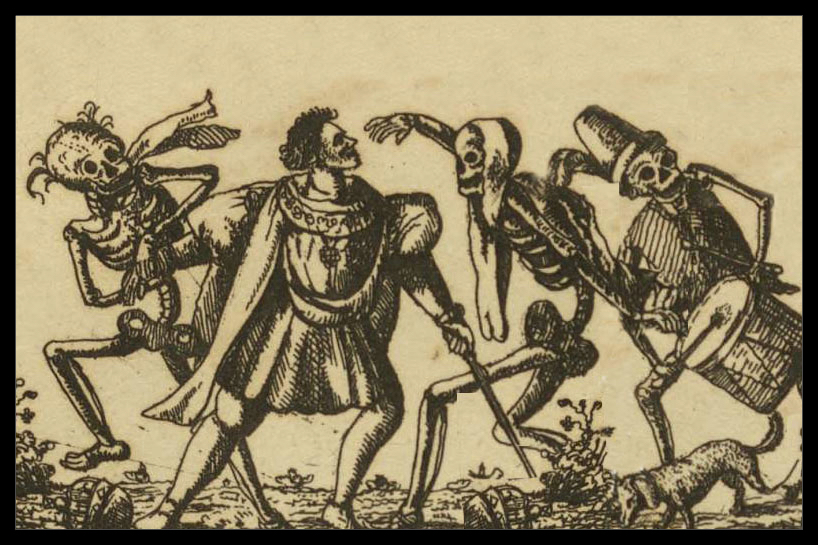

Reflecting on reading Vonnegut’s thoughts about life means far more today than it did decades ago. I came across this comment by Vonnegut, “No art is possible without a dance with death.” Having done the dance twice, I understand how my near-death experiences transformed my life in the positivity most profound manner. If you haven’t done the dance, you can’t grasp the brevity of life. I didn’t until I did the dance.

This is the other comment that I fully understand. Vonnegut wrote, “Writers can treat their mental illnesses every day.” All my writing is Rogerian psychotherapy as both therapist and patient. Again, Vonnegut is correct.

I write to resolve the disconnects in my Weltanschauung. As I look out upon my world, I can’t honestly grasp the nonsense facing America and the world today. I’m fully cognizant that all Americans aren’t going to agree with each other on a litany of problems facing us today.

No society has ever been of one accord. There will always be naysayers on all sorts of issues. However, America is bifurcated. I grasp issues like whether we should keep daylight savings time or whether college athletes should be paid while in college. I could argue the pros or cons of both issues.

Nonetheless, the issues that divide us today are far more significant. Hey, I’m an 80-year-old white guy, and I can see it. What rattles me is that others don’t see the obvious. America hasn’t dealt with racism. Enslaving humans started a century and a half before we became a nation. We fought the Civil War over that issue, which didn’t resolve the issues that many whites have issues with blacks and now other minorities. Call it racism or white supremacy; it is still wrong.

The issue of sexism predates racism. It wasn’t until 1920 that women could vote in a national election. What’s with the weaker sex? On average, when it comes to body mass, men are dominant. But women conceive, bear, and raise that child.

Regarding IQs, today’s medical schools have 54% female students. In veterinary schools, the number is 80%. Entrance to either type of medical school isn’t based on the public’s votes. Going to either medical school is based on grades and test scores. When it comes to getting elected to public office, it is based on elections. The percentage of women in the Senate is 25%, and in the House, it is 29%.

Those stats aren’t good if we want to prove that women are equal to men in our society. Even more atrocious is that men write laws determining the reproductive rights of women.

Other societal issues that America needs to face include addressing the rights of the LGBTQ community, resolving poverty, xenophobia, and the list goes on. We live in troubling waters; many don’t care, or they think discrimination is fine.

What fascinates me is that Kurt Vonnegut and William Faulkner addressed the same problems.

Faulkner was one of the great American writers of the first half of the 20th century. His writing career started with writing poetry but then moved to short stories. It wasn’t until 1927 that Faulkner wrote his first novel. Two decades later, in 1950, he traveled to Stockholm to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature. This is the last section of his short acceptance speech.

I decline to accept the end of man. It is easy enough to say that man is immortal simply because he will endure: that when the last ding-dong of doom has clanged and faded from the last worthless rock hanging tideless in the last red and dying evening, that even then there will still be one more sound: that of his puny inexhaustible voice, still talking. I refuse to accept this. I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet’s, the writer’s, duty is to write about these things. It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past. The poet’s voice need not merely be the record of man, it can be one of the props, the pillars to help him endure and prevail.

Faulkner expressed the duality that America is experiencing and what I feel personally. At the national level, Trump and his mini-me, Guiliani, face the onslaught of indictments and trials. Both claim they are as innocent as the new fallen snow on Christmas Eve.

At a more personal level, I am merely a microcosm of what is happening nationally. In my minuscule place in the grand scheme of things, I face obstacles that make as much sense as what is happening nationally. Faulkner said in his acceptance speech, “I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance.” When facing my quest, I survive on Faulkner’s words. When you are on your quests in life, ask a simple question. Who will benefit the most if you succeed? If you answer that you will, you might want to rethink your drive and motivation. It is in giving that we get.

This is Faulkner’s brief speech after receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature. Interestingly, reading his speech is far superior to hearing it. See what you think.

I feel that this award was not made to me as a man, but to my work—a life’s work in the agony and sweat of the human spirit, not for glory and least of all for profit, but to create out of the materials of the human spirit something which did not exist before. So this award is only mine in trust. It will not be difficult to find a dedication for the money part of it commensurate with the purpose and significance of its origin. But I would like to do the same with the acclaim too, by using this moment as a pinnacle from which I might be listened to by the young men and women already dedicated to the same anguish and travail, among whom is already that one who will some day stand where I am standing.

Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it. There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only one question: When will I be blown up? Because of this, the young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make skillful writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat. He must learn them again. He must teach himself that the basest of all things is to be afraid: and, teaching himself that, forget it forever, leaving no room in his workshop for anything but the old verities and truths of the heart, the universal truths lacking which any story is ephemeral and doomed—love and honor and pity and pride and compassion and sacrifice. Until he does so, he labors under a curse. He writes not of love but of lust, of defeats in which nobody loses anything of value, and victories without hope and worst of all, without pity or compassion. His griefs grieve on no universal bones, leaving no scars. He writes not of the heart but of the glands.

Until he learns these things, he will write as though he stood among and watched the end of man. I decline to accept the end of man. It is easy enough to say that man is immortal because he will endure: that when the last ding-dong of doom has clanged and faded from the last worthless rock hanging tideless in the last red and dying evening, that even then there will still be one more sound: that of his puny inexhaustible voice, still talking. I refuse to accept this. I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet’s, the writer’s, duty is to write about these things. It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past. The poet’s voice need not merely be the record of man, it can be one of the props, the pillars to help him endure and prevail.