Be Careful What You Teach

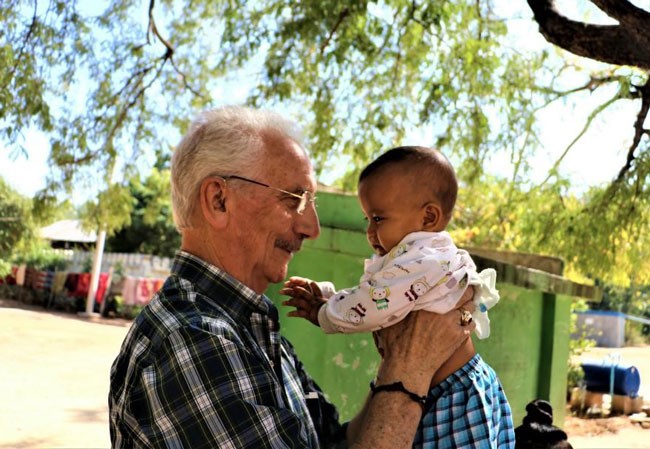

This essay picks up on what I call one of my idiosyncrasies. I have a tendency to gravitate to young children. Some of the children are too young to recall me, and most I probably won’t see again. That doesn’t concern me. What does concern me is that the child senses that some old guy cares about them. I’m happy if I can make them smile. If I can make them laugh, I’m delighted. This photo shows my great-granddaughter and me smiling at each other when we met. Her name is A Ngal Lay, which means, in Burmese, the little one.

Moh Moh was my tour guide a decade ago near Inle Lake in Myanmar. Her husband, Ko Ko, was my guide on my second trip. They are my children, and their three children are my grandchildren. Moh Moh knew that I loved to visit open-air markets. I never mentioned my fixation with young children to her. She realized it by merely watching me. I took loads of photographs of pagodas and scenery around Inle Lake.

However, one of the reasons that I love open-air markets is the various stalls where people sell produce, fish, meat, or spices. Most of these stalls also included the young children of the seller. It fascinated me to see the little ones. Therefore, my desire to communicate with young children can be traced to events like the snowman.

My follow-up to the snowman essay was becoming a Bo Bo Gyi. Both of those articles dealt with reaching out to young kids. I wanted my readers to replicate my reaching out to the little ones regardless of whether or not they knew the children. I wanted them to leave a message with the child...someone saw value in them. All children go through the process called infantile amnesia or later childhood amnesia. In infantile amnesia, before three, children don’t recall experiences. There is some retention of children starting around three to six. As the child gets to ten, more is recalled. Experts in this field of research vary somewhat in terms of the child's age, retention, and why.

Nonetheless, most children will lose their ability to recall but not necessarily lose their memory. That paradox haunts me. Memories of A Ngal Lay and our first encounter are probably present in her brain, but she can’t recall them. Amnesia is probably not the best word to define that childhood experience. It isn’t so much the loss of memory but the loss of being able to recall an event, which is stored in the deep recesses of a child’s brain.

For decades, I misdiagnosed what I call one of my idiosyncrasies. All human actions are predicated based upon a cause. My fascination with young children has roots in my grandfather making a snowman. Other causes were generated by moving to Mt. Lebanon and dancing with death twice. My parents moved from Pennsauken, NJ, a lovely middle-class community and schools, to Mt. Lebanon, the wealthiest community in Western Pennsylvania and the 19th-best school system in the country. I learned two things at Mt. Lebanon; I was dumb and poor. Those learnings were my mistakes due to moving into a golden ghetto.

My two dances with death also affected my Weltanschauung or worldview. One of the dances was due to falling off a ladder and hitting my head against a retaining wall. It caused a subdural hematoma, which was bleeding within my brain. I was in ICU and a rehab hospital for nearly two months. I don’t recall the fall, going to the hospital, being transferred to a rehab hospital. I remember only the last week in the second hospital.

Essentially, I needed to start my life all over. When I got home, I needed to exercise. I had spent most of two months in a hospital bed. The first time I wanted to walk around the lake after returning home was a failure. I walked from the front door to the sidewalk, less than 50 feet. That was a walk too far. Nevertheless, over the next few weeks, I began the process of rebuilding my physical strength.

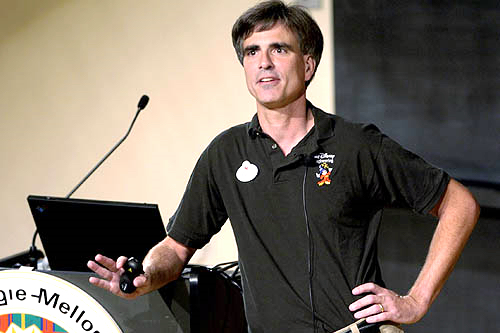

I had done the dance with death, but I didn’t realize the transformation in me for several years. By sheer happenstance, I had dinner with Mike Schmitt, who I hadn’t met before. He observed my hyper personality and asked whether I had heard or watched The Last Lecture? I hadn’t. Mike sent me a link to Randy Pausch’s Last Lecture.

The message that my grandfather sent me, realizing that I wasn’t dumb and poor, and my dances with death transformed me during my journey down the yellow brick road. Trump wasn’t as fortunate as I was to have a father or grandfather like mine. Therefore, the messages left in the Donald’s brain weren’t good and caring. So, Trump wasn’t raised in a loving and nurturing atmosphere. Hence, it explains why Trump acts like a narcissistic nerd.

This is a photo-op for Donald the Dumb.

This isn’t an old guy caring for two infants; it is a photo op.

Trump’s message about himself caused his inane mindset. Donald the Dumb is so dumb that he can’t process that his parents made major mistakes when Trump was an infant. He merely compensates for his feeling of insecurity, which creates his narcissistic personality disorder. Or as my maternal grandmother said, “I love me, I think I’m grand when I go to heaven, I’ll hold my hand.”

Watch this video of several fathers and their young children. As a youngster, Trump has never experienced joy and love from his father.

We learn our value as human beings via our relationship with our parents and grandparents. Think about reaching out to the youngsters in your family and those beyond your extended family. We are all family members of each other.