|

I'm not sure what captured my imagination the first time that I heard the title of Hemingway's classic, The Snows of Kilimanjaro. I suspect it was the alliteration of the "o" sound in the title. However, it wasn't too long after first hearing of the book that I was reading about Harry, Hemingway's protagonist, and his preoccupation with death. Many years have come and gone since I traveled through the pages that tell the tale of a tragic death in Tanzania with the backdrop of the snows of Kilimanjaro. I devote my pre-retirement years to teaching, and when I am not teaching, I want to travel and write about places and peoples that I read about when I wore the clothes of a younger man. After an upcoming trip to Southeast Asia and one to Peru, I would like to visit southeastern Africa and hope to see snow-capped Mt. Kilimanjaro. Therefore, you can imagine my concern when I read that the snows will completely melt away in a dozen years. If I'm ever going to gaze upon that white-capped mountain in person, I'd better book that trip very soon. The snows of Kilimanjaro are really the glacier of Kilimanjaro (see, glacier doesn't have the same ring to it). The glacier was put down nearly 12,000 years ago when Africa was a very wet and different place than it is today. However, the snows are melting away and changing Mt. Kilimanjaro. In the last century, the mountain lost 80% of its snow cover. Since I started college in the early 60s, the mountain has changed a great deal. The glacier's height has been reduced by 56 feet during my adult life. Experts predict that in a dozen or more years, Mt. Kilimanjaro will go completely bald. Many people are concerned about what is happening. The snows are the source of much needed water for the surrounding area. When the snows aren't naturally replenished, the lives of many that depend on the water are adversely affected. This drip-down effect hurts all those that depend upon Mt. Kilimanjaro for a constant supply of water and tourist money. Scientists also will lose a valuable time capsule of African history, which is encased in the ice that goes back to Paleolithic times. That rich historic record that predates written records is quickly thawing away. Some concerned scientists want to try anything to stop or at least to slow down this scientific and scenic meltdown. One of the more bizarre ideas is to place a very large tarpaulin over the glacier that would reflect the sun's destructive rays away from the precious ice mass. (Where is Christo when you need his landscape artistry?) The vanishing snows of Kilimanjaro is an example of life imitating art. In Hemingway's novel, Harry is a would-be writer wrestling with the reality of his death-before he has accomplished his literary dreams. It is obvious that Harry in the novel and Hemingway in real life have much in common, as they deal fearfully and often awkwardly with the inescapable fact that death faces both of them. Harry (and Hemingway) sees the hyena circling the camp and he knows that ultimately, he can't stop the inevitable-death is coming. As Harry goes through the stages of dealing with his death, the snows continue to melt as a metaphor for Harry, Hemingway, and for all of us. Even if we can stave off death with our versions of tarpaulins on glaciers, time marches on and death will ultimately win. Instead of attempting to fend off death, perhaps we need to learn the lesson for the snows of Kilimanjaro-from both the novel and from reality. Since death can't ultimately be stopped, we need to live the life we have to the fullest as long as we have life. Affirming life and those around us are the best ways to find meaning in the fleeting experience that we call life. As 2003 slowly dies and Kilimanjaro's snows slowly melt, affirm the ultimate gift of life that is here today but may be gone tomorrow. This article appeared in the Dixon Telegraph on 12/30/03.

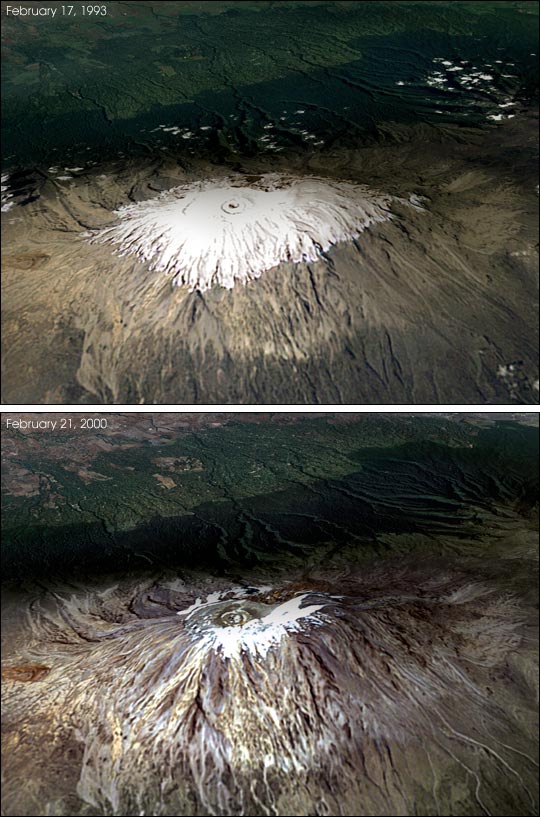

NASA pictures--before and after the massive melting

|