“You’re a Better Man than I Am, Gunga Din!”

Last week, I happened to come across an essay about Rudyard Kipling while researching Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. I noted it but delayed posting this as the second essay in June. The first writing this June was my poem to Ti Ti, my granddaughter, who turned twenty. That event is more critical than an article about Kipling. That was backstory; now, for Kipling.

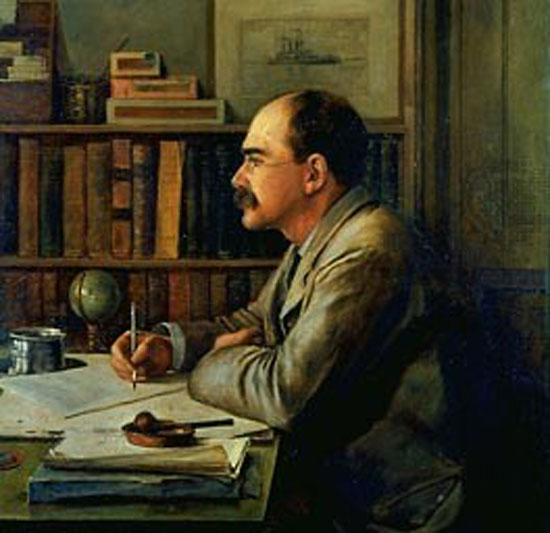

Kipling was an excellent writer in both poetry and prose. His technique and storyline were done very well. However, once I went beyond his writing style, it troubled me. He was into British imperialism. He wrote The White Man’s Burden as a poetic means to influence America to deal with the Philippines by following the British mindset. The Brits loved conquering other peoples and nations, which was both racist and white supremacist by their imperialistic nature.

Before this week, I knew many of Kipling’s works reflected racism, but I was unaware of his life. He was born in 1865 in Bombay, India. His father was an artist and a professor at an art school, and his mother came from a prominent British political party. Two Indian locals cared for Kipling. They would tell Kipling stories in Hindi. For his first five years, Kipling enjoyed life in India.

However, the British, who worked in the colonial government, taught, or worked in other jobs, would have their children raised in England. Kipling lived in an English boarding home called the House of Desolation. Sarah Holloway was now Kipling’s acting mother. She was an evangelical Christian who was both physically and mentally abusive toward him. Looking back upon his time at the House of Desolation, he wrote the novel Baba Black Sheep as a seeming autobiography.

Kipling’s mother took him away from the House of Desolation as soon as she realized what he had gone through. Kipling entered a prep school in 1878 for boys who would join the army. After that period, he finally returned to Bombay, India. It wasn’t long before he was a writer for a couple of British colonial papers. During those years, Kipling wrote and published several dozen books. In 1889, he left India to return to London. He took a circuitous route, starting in Burma, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Japan, before moving to America and Canada. Kipling worked his way east, stopping in Chicago, Washington, and New York. After visiting nearly everything between Bombay and London, he finally arrived in London.

In 1892, Kipling, in the “thick of an influenza epidemic,” married and moved to Vermont. He authored Jungle Books, Captains Courageous, Mandalay, and Gunga Din during that time. These are a few verses from Mandalay.

Over several years in New England, Kipling and his wife had Josephine and Elsie. For various reasons, from within and outside the family, Kipling and his family returned to England, where John, his son, was born in 1897. During that time, Kipling wrote The White Man’s Burden.

Kipling and Josephine contracted pneumonia while visiting the States. Josephine died, but Kipling survived by writing additional books and receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1907.

Kipling’s third child, John, was 18 when he enlisted in the Irish Guards during WWI. Soon after reaching France, John Kipling was one of 60,000 British troops killed in the Battle of Loos in France, which is located at the northern tip of France close to the Belgium border. That loss, coupled with Josephine\'s death, devastated Kipling.

Kipling used writing throughout his entire life to deal with loss and suffering, from the days at the House of Desolation, the death of Josephine, to John’s death in the Battle at Loos.

Kipling also had issues with racism. George Orwell wasn’t into racism but wrote about hearing of Kipling’s death, “I worshipped [him] at thirteen, loathed him at seventeen, enjoyed him at twenty, despised him at twenty-five and now again rather admire him.” Orwell saw, in advance, the fall of the British Empire, beginning with the passing of Kipling in 1936.

I also parallel Orwell’s mindset regarding Kipling. My symbol of Kipling’s racism was his poem Gunga Din. The poem concerns a British colonial officer and his servant, Gunga Din. Essentially, the officer mistreated Din. Din, for some reason, accepted being the officer’s slave. Kipling concluded the poem with this stanza

You Lazarushian-leather Gunga Din!

Though I’ve belted you and flayed you,

By the livin’ Gawd that made you,

You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din!

Indeed. Din was a better man than most of the British colonial population. We need to learn from Kipling about not having the holier-than-thou mindset.

This is a collection of Kipling’s poems.