A Lesson Taught by Dylan Thomas

In my twilight years, I noticed some quirks. I often follow up on previous essays. This article is an example. I was thinking about the two poems I gave Dr. Garritson for her twin boys, who are due around Christmas. As I was rereading that essay after it was posted to my website, I thought about another poem, Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night, by Dylan Thomas.

Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night

He wrote the poem for his father but also wanted his readers to grasp it.

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Thomas’ poem about rage is probably his most popular poem. His poem was an excellent example of the villanesque style. The poem addresses four types of people facing their deaths: the wise men, the good men, the wild men, and the grave men.

Dylan disses the wise men who are facing death. They consider themselves wise when their words haven’t really amounted to anything. They haven’t done anything which was like lightning. Dylan tells these people, “Do not go gentle into that good night.”

The second set is what Thomas good men. These people were well-intended but failed to make much from their lives. He tells them, “Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

The third group consists of wild men. Thomas sees himself as one of the wild ones. He drank a lot but also produced a lot.

The last group is the grave men. This group also includes Thomas. They are in their twilight year, but there is still time to contribute to life. So, to them, he writes, “Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

While The Bridge Builder and If... are quiet and reaffirming literary masterpieces, Thomas’ poem is about shouting to the world. Act now. Don’t waste the time you have. Death will arrive before you get into gear.

One of the benefits of one’s twilight years has to do with the colors of life. If you want to take a great photograph, do it just before the sun goes down. It is also true if you wish to paint a great painting, like William Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire, do so toward the evening.

In my twilight years, I fully understand what Thomas wanted his readers to grasp after reading. In the grand scheme of things, I parallel Thomas in his last two positions: the wild men and the grave men.

For years, I have written about my two dances with death. I don’t need to have the bells toll for me. Trust me. I know that my clock is ticking. Additionally, I also know, both factually and emotionally, that my clock is ticking. That puts me in a bind. I can’t waste the time I do have and not realize the promise that I made to Ti Ti. A decade ago, I met Ti Ti near Inle Lake, Myanmar. She was nine and wanted to play Scrabble with me.

I left her home that day, realizing I had met my granddaughter. That changed my Weltanschauung. I have seen things differently since then. Her two younger sisters are also my granddaughters, and her parents are my children.

Because of COVID and the coup, my promise to provide her with a college education would require her to get a student visa. She would live at my home and attend college close to where I live. However, she has been rejected three times. She never got an answer to why.

Therefore, I am fully aware that my clock is ticking. I also have raged against the dying of the light. Thomas would be proud of me. I have tried various means to contact the charge d’affaires at our embassy in Myanmar. Nonetheless, the gatekeeper won’t forward my request to the head of the embassy, and I have failed.

There are three takeaways that I want Ti Ti to understand.

- The first is that Ti Ti is worth everything I have done to assist her in her efforts to get her college education in the States and return to make her country a better place to live. Regardless of what the next couple of weeks hold for her, she knows that her Papa Al sees her as an exceptional and gifted young lady.

- The second takeaway is that I will not stop trying unto she is granted a student visa. I know Thomas’s feeling when he wrote, “Rage, rage, against the dying of the light.” I won’t fail my granddaughter.

- Finally, on January 20.2043, which would have been my 100th birthday, Ti Ti will give her children copies of Dylan Thomas’ poem, Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night. She will tell them about a crazy old American who discovered his family in Myanmar. Ti Ti will tell them stories about the fun times we had as a family many years ago. Additionally, she will tell them how much he believed in her as a person and student.

An addendum.

Ti Ti, I need to tell you some time that I am proud of you.

Love,

PaPa Al

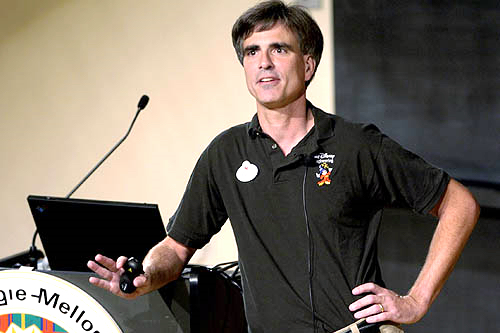

Dylan Thomas is reading his poem, Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night.