|

Al: I teach a philosophy class for the University of

St. Francis, and we have lengthy discussions on capital punishment. I have also

written many articles on the subject, but I would like to have you talk with me

about your feelings of the subject. However, I need you to give me a quick

thumbnail of who Rob Warden is, where he was born, grew up, and went to school.

Al: I teach a philosophy class for the University of

St. Francis, and we have lengthy discussions on capital punishment. I have also

written many articles on the subject, but I would like to have you talk with me

about your feelings of the subject. However, I need you to give me a quick

thumbnail of who Rob Warden is, where he was born, grew up, and went to school.

Rob: I was born in a little town called Carthage,

Missouri. People about our age might be familiar with it as the crossroads of

Route 66 and 71. Almost anyone who was going from the east to the west or from

the north to the south passed through Carthage. When I was in high school, I

actually worked at a filling station right at that intersection-actually, there

were four filling stations at that intersection! I went from there to the

University of Missouri and Pittsburg State University in Pittsburg, Kansas. I

left there as a senior to take a job with the newspapers in Michigan. I worked

primarily at the Kalamazoo Gazette for a couple of years, and then I

became a science writer at the Chicago Daily News in 1965. I did fairly

well in journalism becoming the assistant financial editor of the paper, and

then ultimately the assistant national editor and the night city editor. It

wasn't long before I became a foreign correspondent and was in the Middle East

and Europe in the mid 70s. I had a rather dramatic escape from a hotel in

Beirut at the height of the internal strife in Lebanon. I don't think that they

were even yet calling it a civil war. From my perspective, it was a civil war!

My interest in investigative reporting had caused

me to gravitate toward the law and lawyers as sources. When the Chicago

Daily News folded in 1978, I worked very briefly for the Washington Post

and then had an opportunity to start the publication, Chicago Lawyer,

where I was the editor and published it for ten years. We were really the first

to start writing about the wrongful conviction problem. Others merely wrote it

off as something that was just a sort of an anomaly of a well-functioning

system. However, these few flaws affected thousands, maybe as many as 100,000

people in America who are imprisoned at any given time for crimes that they

didn't commit.

My interest in investigative reporting had caused

me to gravitate toward the law and lawyers as sources. When the Chicago

Daily News folded in 1978, I worked very briefly for the Washington Post

and then had an opportunity to start the publication, Chicago Lawyer,

where I was the editor and published it for ten years. We were really the first

to start writing about the wrongful conviction problem. Others merely wrote it

off as something that was just a sort of an anomaly of a well-functioning

system. However, these few flaws affected thousands, maybe as many as 100,000

people in America who are imprisoned at any given time for crimes that they

didn't commit.

No one had ever approached it in that

manner before. There had been some other very good efforts on convictions: Gene

Miller at the Miami Herald has done great work and a group of reporters

had done some work on a New Mexico case. But, once again, they are just sort of

hung out there like, "Oh, gee, isn't it terrible that this happened," but few

got excited about it. After all, it's very rare.

Some even said, "This guy is probably not innocent,

but this is just one of those cases in which we can't meet our burden of proof

beyond a reasonable doubt. You know, this is the best system in the world, but

no system of course is perfect. Nevertheless, this guy is probably guilty as

charged. If he is innocent, boy that's terrible, but rest assured this would be

a very rare occurrence."

Some even said, "This guy is probably not innocent,

but this is just one of those cases in which we can't meet our burden of proof

beyond a reasonable doubt. You know, this is the best system in the world, but

no system of course is perfect. Nevertheless, this guy is probably guilty as

charged. If he is innocent, boy that's terrible, but rest assured this would be

a very rare occurrence."

Well, it's not a rare occurrence. In fact, our

experience here in Illinois, of the 289 men and women (five were women)

sentenced to death between 1977 and 2003, that Governor Ryan commuted their

sentences, 17 of them have been shown to be innocent and have been exonerated.

They are today legally innocent. That is an error rate of 5.6%, and it is

absolutely intolerable. If we look at that and see the error rate is 5%, that

means that out of the 2 million people in prison, that would mean that there are

100,000 innocent people in prison at any given time.

Al: What would the error rated for capital cases?

Rob: In Illinois capitol cases, I am confident that

the error rate probably holds true across the country, is approximately 10%.

That means that for every ten people that we have executed, it is very likely

that one of those people was innocent. The scary thing about it is that the

guilt or innocent issue is just the threshold when it comes to capitol cases.

It is still being applied in an arbitrary, capricious, wanton, freakish, and

racially discriminatory manner. If you look at the city of Chicago for

instance, only 6% of the murder victims in this city are white, and yet, more

than 50% of the people who are on death row for murders that occurred in the

city of Chicago, are there for killing white victims. Now, the people on the

other side will say, well, that doesn't really prove anything, maybe these

crimes were qualitatively worse, but I don't think so. I mean, that might

explain a minor discrepancy. Perhaps cross-racial crimes are more violent and

tend to be worse than crimes committed by people of the same race, but I don't

think so. Even if this were so, it is not going to account for that 10 to 1

disparity that I just described.

The other phenomenon is that they arrest some kid,

the kid is in the county jail, and he has been there for six months awaiting

trial. The prosecutors say, "Look if you plead, we will recommend a one year

sentence. You can basically walk out the door; here is the key to your cell."

If the kid says that he is innocent, then they say, "Well, if you are found

guilty, then you will have to do for five years. Do you want that or do you

want to take our deal here?" That is the insidious plea bargaining dilemma. It

is really a modern form of torture. Usually, if you want to get a handle on the

problems that we have in society, we just set our social scientists loose to go

out and do a survey. For example, do you want to know how much unreported rape

there is? We go out and survey women. "Have you ever been raped? Did you

report it to the police?" Then we publish the results. We can't go into a

prison and say, "Hey, how many of you guys are innocent?" There is no way to

prove the percentage of innocent. We have to look for other means rather than

conventional social science techniques to get a handle on how serious this

problem is. Whether it is 5%, 10%, or even 1%, it's still a serious problem.

The other phenomenon is that they arrest some kid,

the kid is in the county jail, and he has been there for six months awaiting

trial. The prosecutors say, "Look if you plead, we will recommend a one year

sentence. You can basically walk out the door; here is the key to your cell."

If the kid says that he is innocent, then they say, "Well, if you are found

guilty, then you will have to do for five years. Do you want that or do you

want to take our deal here?" That is the insidious plea bargaining dilemma. It

is really a modern form of torture. Usually, if you want to get a handle on the

problems that we have in society, we just set our social scientists loose to go

out and do a survey. For example, do you want to know how much unreported rape

there is? We go out and survey women. "Have you ever been raped? Did you

report it to the police?" Then we publish the results. We can't go into a

prison and say, "Hey, how many of you guys are innocent?" There is no way to

prove the percentage of innocent. We have to look for other means rather than

conventional social science techniques to get a handle on how serious this

problem is. Whether it is 5%, 10%, or even 1%, it's still a serious problem.

Al: Whatever the percentage is, how would you break

it down?

Al: Whatever the percentage is, how would you break

it down?

Rob: There are different levels of the causes of

wrongful convictions. Fundamentally, in almost every wrongful conviction about

which we know, there has to be police or prosecutorial misconduct, but it

becomes a very hard thing to quantify. Unless you have an appellate court

finding or something like that, which finds police or prosecutorial misconduct;

it is very hard to prove. I have been looking at the ones that are

quantifiable. If we can prove by DNA that somebody did not commit the crime,

and there were eyewitnesses who placed him at the scene or placed him with the

victim or sometimes the victim's own identification, then it's quite clear, that

the identification testimony was simply wrong. The same thing is true of if

there was junk science in the case or if there is a false confession.

Al: Why would someone confess to a crime that he didn't commit?

Al: Why would someone confess to a crime that he didn't commit?

Rob: That is an interesting question, that I can deal

with in a minute if you want, but let's look at junk science. Suppose that

there was hair evidence, there was something that was presented that appeared to

be exculpatory but wasn't. Therefore, it was either false or misleading

forensic science. There can be no dispute upon these factors. The jailhouse

snitch and false confessions are other important areas of concern. Most people

cannot understand or appreciate these false confession phenomena. They can't

imagine that a person could ever confess to a crime that a person didn't

commit. Not a month goes by that somebody doesn't walk into an L.A. police

station and announces, "I killed the Black Dahlia" or "I killed Nicole Brown

Simpson." They are crazy people, and we understand that people can be tortured,

and as we know has happened in the city of Chicago. In the State of Illinois,

we have had about forty-five documented wrongful convictions in murder cases.

Confessions or exculpatory statements somehow affected twenty-six of those-that

is literally more than 50% of the cases. Now, this wasn't always the confession

of the guy himself. Sometimes, it was the confession of an accomplice or a

jailhouse snitch testifying in return for leniency for him or herself. However,

there are a lot what appear to be confessions that almost appear to be

voluntary.

A very good example would be the case of Gary

Gauger in McHenry County, Illinois. Gary was convicted and sentenced to death

for the murder of his parents, a crime for which the prosecution contended he

confessed. Gary always denied that he confessed or intended to confess, but the

circumstances were that he wakes up in the morning and finds his father

apparently dead. He calls 911, they come and soon find his mother dead. Gary

is the only person around and naturally is a suspect. They take him in for

questioning, and after twenty-seven hours of interrogation, they claim that Gary

confessed. Now, Gary's story is somewhat different. He says that the police

told him that they found bloody clothes and a knife in his room, and that he had

to have done it. He must have done it somehow and then blacked out, and that's

why he doesn't remember it. After twenty-seven hours, Gary starts thinking that

the police must be correct. Maybe, he blacked out and doesn't remember it. The

police tell me that it is a common phenomena, somebody does something like this,

in the midst of momentary insanity and blackout. Then they tell Gary just start

hypothesizing about how you might have done it. How would he do it if he had

murdered his parents? Maybe thinking about it would jar your memory, and it

will all come back to him. Gary finally starts thinking he did it. Then there

was a jailhouse snitch who claimed that Gary confessed the whole thing. That's

the evidence that convicted and sent Gary Gaugher to death row.

A very good example would be the case of Gary

Gauger in McHenry County, Illinois. Gary was convicted and sentenced to death

for the murder of his parents, a crime for which the prosecution contended he

confessed. Gary always denied that he confessed or intended to confess, but the

circumstances were that he wakes up in the morning and finds his father

apparently dead. He calls 911, they come and soon find his mother dead. Gary

is the only person around and naturally is a suspect. They take him in for

questioning, and after twenty-seven hours of interrogation, they claim that Gary

confessed. Now, Gary's story is somewhat different. He says that the police

told him that they found bloody clothes and a knife in his room, and that he had

to have done it. He must have done it somehow and then blacked out, and that's

why he doesn't remember it. After twenty-seven hours, Gary starts thinking that

the police must be correct. Maybe, he blacked out and doesn't remember it. The

police tell me that it is a common phenomena, somebody does something like this,

in the midst of momentary insanity and blackout. Then they tell Gary just start

hypothesizing about how you might have done it. How would he do it if he had

murdered his parents? Maybe thinking about it would jar your memory, and it

will all come back to him. Gary finally starts thinking he did it. Then there

was a jailhouse snitch who claimed that Gary confessed the whole thing. That's

the evidence that convicted and sent Gary Gaugher to death row.

The very first wrongful conviction that I ever saw

was in the early 80s. It was on the south side

of Chicago and involved a young

man named Lavell Bert. You can read about him on our website. Lavell had just

been convicted of a murder of a child. This happened near what was then Comiskey Park. A child is standing in the front door of his home and he is shot

dead. Lavell Bert confessed to this crime. The story that he told is quite

persuasive. He was intimidated by some rival gang members. So, he went home to

get a gun to protect himself. When he saw the rival gang members running down

the street, he fired a shot at them and missed. He did hit this child standing

in a doorway. He then ran down the street and threw the gun away. Of course,

they never found the gun, for good reason. However, Lavell confesses and is

convicted. Very shortly after the conviction, the grandmother of the victim

calls the judge and says, "Your honor, I think there has been a terrible

mistake. I found the weapon that I believe killed my grandson, and it was in my

daughter's bureau drawer. She has admitted to me that this was an accidental

shooting, and that she made up this story because she didn't want to admit what

had happened. She never thought that anybody was going to be charged and

convicted. She has now told me the whole story."

The very first wrongful conviction that I ever saw

was in the early 80s. It was on the south side

of Chicago and involved a young

man named Lavell Bert. You can read about him on our website. Lavell had just

been convicted of a murder of a child. This happened near what was then Comiskey Park. A child is standing in the front door of his home and he is shot

dead. Lavell Bert confessed to this crime. The story that he told is quite

persuasive. He was intimidated by some rival gang members. So, he went home to

get a gun to protect himself. When he saw the rival gang members running down

the street, he fired a shot at them and missed. He did hit this child standing

in a doorway. He then ran down the street and threw the gun away. Of course,

they never found the gun, for good reason. However, Lavell confesses and is

convicted. Very shortly after the conviction, the grandmother of the victim

calls the judge and says, "Your honor, I think there has been a terrible

mistake. I found the weapon that I believe killed my grandson, and it was in my

daughter's bureau drawer. She has admitted to me that this was an accidental

shooting, and that she made up this story because she didn't want to admit what

had happened. She never thought that anybody was going to be charged and

convicted. She has now told me the whole story."

Well, they checked ballistics, and it was the gun.

I will never forget it. I called Lavell Bert with his lawyer's permission to

let me interview him, and I said, "Lavell, why did you confess?" I couldn't

imagine what did to him to make him confess. Did they put him on a rack, or did

they put a typewriter cover over his head? I'm expected to get a horror story

about how the Chicago police extracted this false confession from him. That's

not what happened. Lavell said, "They slapped me around a little bit, but

that's not why I confessed. They told me that these two girls told them this

story, and I could hear the girls in the next room. They were laughing.

Finally, one of the officers comes in and says, "Look Lavell, everybody knows

that you are no baby-killer, and if this was an accident, we will be able to

clear this up, and you will be able to go home this afternoon." After seven

hours of interrogation, Lavell Bert could repeat back all the facts that the

police just gave him. This is a very common phenomenon.

In the case of Aaron Patterson, he had been

tortured and finally agreed to confess. However, with a paper clip he found in

the interrogation room, he carved into the bench he was sitting on, "I have been

tortured to confess." Then they brought in the State's Attorney to take the

confession that they have gotten him to agree to make, and he refuses. There

was simply no more reason to believe that he did it, than to believe that anyone

of a half a million other people in the area could have committed this crime.

There was no reason whatsoever. They convicted and sentenced him to death based

on a fabricated confession, a torture confession.

In the case of Aaron Patterson, he had been

tortured and finally agreed to confess. However, with a paper clip he found in

the interrogation room, he carved into the bench he was sitting on, "I have been

tortured to confess." Then they brought in the State's Attorney to take the

confession that they have gotten him to agree to make, and he refuses. There

was simply no more reason to believe that he did it, than to believe that anyone

of a half a million other people in the area could have committed this crime.

There was no reason whatsoever. They convicted and sentenced him to death based

on a fabricated confession, a torture confession.

Sometimes, there are confessions that they have

tricked you into making, sometimes they are confessions that they simply

fabricated because all of their other techniques failed, and then this gross

bunch like Burge that literally torture people into a confession. No matter

what we do in the system, we can't reform the system. There is no way to

prevent people from deceiving the system-there is simply no way. That is one of

the reasons why I think we have no choice but to abolish the death penalty. As

horrendous as it is, people can be convicted, imprisoned, and lose their freedom

based on this kind of evidence. That's why I think we will ultimately abolish

the death penalty-it is only a matter of time.

Al: How was it that George Ryan imposed a moratorium

of the death penalty?

Al: How was it that George Ryan imposed a moratorium

of the death penalty?

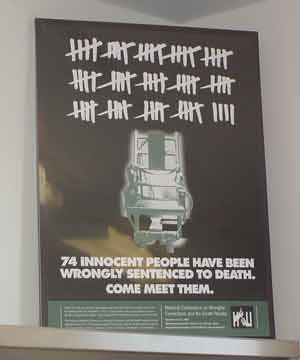

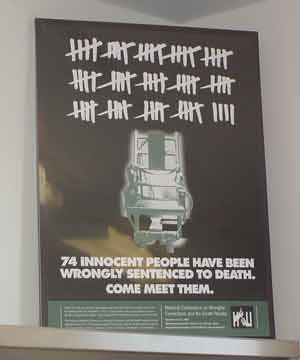

Rob: We had this conference here in 1998. It was the

first national conference on wrongful convictions and the death penalty. This

was the first time that we ever really got the national and international media

to see that this was really a systemic problem and not just this anomaly. The

media was able to see these people, touch them, shake hands with them, and

interview them. We had more than thirty of them here at the Northwestern Law

School. Two months after that conference, Anthony Porter had forty-eight hours

to live. He had been measured for his burial suit and had ordered his last

meal. We were able to persuade the Illinois Supreme Court to grant a stay on

the ground that he had such a low I.Q. that he literally might not be capable of

understanding what was about to happen to him or why.

Anyone who has seen Anthony Parker interviewed would

think that he wasn't that impaired. He only tested like 68-72 on various IQ

tests. Sometimes, people have very low IQs but are very good at compensating,

and I think that Anthony Parker is one of these people.

At any rate, we get his execution delayed, because

of the delay, journalism students working under David Protest and a private

investigator, Paul Sealino were able to solve this crime. George Ryan was

aghast; he could have signed off on Anthony Parker's execution and would have

had blood of an innocent man on his hand. This profoundly shook George Ryan.

It was really an epiphany for him, because he trusted the system.

Al: When I interviewed Sen. Paul Simon, we also

talked about capital punishment. He asked me, "Do you feel safer driving

through Illinois or Texas? One doesn't have the death penalty and the does. If

capital punishment is a deterrent, then you would feel safer in Texas."

Al: When I interviewed Sen. Paul Simon, we also

talked about capital punishment. He asked me, "Do you feel safer driving

through Illinois or Texas? One doesn't have the death penalty and the does. If

capital punishment is a deterrent, then you would feel safer in Texas."

Rob: In the first place, when you say do you feel

safer, that's probably not the real point.

The real point is--are you safer? Quite clearly, you

are not. In the first place, we only impose the death penalty, that is,

sentence people to death in about 2% of the cases that have come to court in

which the death penalty is an option. If you look at the number of people

sentenced to death in terms of the number of murders, it is less than two tenths

of 1% of all the murders that occur. So in fact, if you just literally let all

of these people go, it would not have an appreciable effect on the safety of

society as a whole. Now, I'm not advocating that, but the numbers are simply

too small to have an appreciable effect on public safety in that respect.

Al: Some see capital punishment having a deterrent

effect.

Warden: If you want to kill me, but you don't want to

do it because this is a death penalty state? The average person who is about to

commit a murder is somehow going to stop and subject his desire to kill to a

cost to benefit analysis and conclude, "Gee, I better not because I could get

the death penalty." That is just absurd. You know they had the death penalty

in England until 1816 for pick pocketing, and it didn't even appear to deter

pick pocketing at the executions of pickpockets! So, it simply doesn't work.

If you want to look at the evidence in the US that the

death penalty isn't a deterrent, take North and South Dakota. S. Dakota has the

death penalty, and N. Dakota does not. The murder rate in S. Dakota is about

30% higher than N. Dakota's.

Common sense tells you that capital punishment tends

to brutalize the society and make murderers of us all. Why do we kill people to

show that killing people is wrong? It doesn't really make a great deal of

sense. If you could show me that every person that we execute in this country,

we deter ten murders, then the argument and the equation might change. Then you

might have a cost to benefit analysis, but there isn't. Therefore, we ought not

to have capital punishment because of the grave risk that is in involved in

executing an innocent person. We have shown that that is a significant

consideration that errors occur in a high number of cases.

Al: As we look around at the rest of the civilized

world, our society stands out.

Rob: Yes, of course, you have to realize that this is

all fairly recent. All of Europe was executing people well after WWII. We are

decades behind them. We certainly don't like being put in with societies like

Iran, Iraq, China, and Saudi Arabia, which are principal practitioners of the

death penalty. I don't think that any of us would feel safer in those

societies. We will join the rest of the Western World at some point; the only

question is when?

Al: Even Turkey wants to get in the EU and will have

to abandoned the death penalty?

Al: Even Turkey wants to get in the EU and will have

to abandoned the death penalty?

Rob: Yes, it's a requirement. You can't get into the EU unless you have abolished the death penalty. Russia and South Africa have

done away with it-almost everywhere else has.

Al: Why is it so appealing to us? Is it the American

frontier mentality?

Rob: No. I don't think that it's the frontier

mentality. As a matter of fact, if you just did public opinion polls on the

death penalty here and in Europe you find that the public perceptions are pretty

much the same. The fact is that horrible crimes occur in our society, and that

horrible people commit horrible heinous crimes. It is very easy in the abstract

if you haven't examined these issues in depth to say, what would be appropriate

for this person? It is easy to understand the impulse, "The guy who did this

should be dead." It is easy for us to understand that! I think we can all

appreciate that. I didn't begin in life as a pathological opponent of capital

punishment. I came to that position, sort of the same way that George Ryan did.

You have to study it, understand it, and see that

there is no benefit to the death penalty. In addition, there are grave risks

involved in it. That's why we ought to abolish it. Most people simply haven't

gone into the issue in this depth. I think American politics tend to discourage

courageous leadership. Our leaders follow the polls. Mr. Dewey said, "Even the

Supreme Court follows the election returns." Well, the election returns are

largely based on uninformed opinion in many issues. That's the situation here

in the States, but it isn't that way in Europe.

You have to study it, understand it, and see that

there is no benefit to the death penalty. In addition, there are grave risks

involved in it. That's why we ought to abolish it. Most people simply haven't

gone into the issue in this depth. I think American politics tend to discourage

courageous leadership. Our leaders follow the polls. Mr. Dewey said, "Even the

Supreme Court follows the election returns." Well, the election returns are

largely based on uninformed opinion in many issues. That's the situation here

in the States, but it isn't that way in Europe.

Al: More informed electorate?

Rob: Yes. I think that the population tends to be

more informed, but then the other aspect of this I think is the racial aspect.

At one time or another, every state or every territory had capital punishment.

In the 20s, some states began abolishing it. I think nine states had abolished

it by 1930. We have thirteen states that still have capital punishment. It's

been rather slow progress, but we are moving in that direction. However, there

is an underlying factor. In the South, they have always thought that we needed

capital punishment to control the blacks. Capital punishments very origins are

pretty much racist, and capital punishment in the South was seen as an advance

from the program of lynching. Then it turned out that the proof required by the

courts was hardly any greater than the proof required by the mob before they

lynched somebody!

Al: And then blacks moved North, and the racism and

need was transported North.

Warden: That's exactly right. So, there are those

two things: our politicians don't really tend to lead and there is this

lingering racial element that motivates capital punishment. This explains the

differences between the US and Europe on this issue.

Al: I have really enjoyed this interview; you have

made a lot of sense.

Al: I have really enjoyed this interview; you have

made a lot of sense.

Warden: I will go anywhere anytime and debate anybody

on the death penalty. Why will I do that? Because, I win every time-not

because I am a good debater, but because I have all the facts. They are on my

side! Every single fact. There is nothing good that you can say about the

death penalty. If you tried to sell death penalty stock on Wall St., you could

be prosecuted for securities fraud!

If you are white, how bad do you think the crime has

to be to get sentenced to death for killing somebody who is black? I tell you,

it has to be absolutely awful. In Illinois, we have five instances of that

happening-a white people sentenced to death for killing black people. You would

have to commit murder in a most heinous manner for a white man to get sentenced

to death for killing a black victim. If you look at the other hand, the typical

case in which the black person is there, most of them are single victims, they

were often felony murders, you know, a robbery at the 7-11 that went awry.

There is just a great difference in the seriousness of these cases.

Al: I teach a philosophy class at the University of

St Francis. It is interesting to hear how my students feel about this issue.

Rob: Gallup has been polling the American public

about the death penalty since 1954, and the polls showed that the vast majority

of people cited that the reason for supporting the death penalty was the

deterrent effect. I did an interview a few years back for an ABC reporter, and

I said, "Do you know we have had this error rate of like 5%, and the guy said,

"Well, 5% isn't bad." I couldn't believe it. Would you get on an airplane if

nineteen out twenty flights made it to their destination?

Al: I'll use that illustration next semester. I also

tell my students that the death penalty desensitizes us when we allow capital

punishment. I think that it adversely affects our society by killing the

humanity within us.

Rob: I think that is correct. There isn't any good

reason for keeping capital punishment.

|

Al: I teach a philosophy class for the University of

St. Francis, and we have lengthy discussions on capital punishment. I have also

written many articles on the subject, but I would like to have you talk with me

about your feelings of the subject. However, I need you to give me a quick

thumbnail of who Rob Warden is, where he was born, grew up, and went to school.

Al: I teach a philosophy class for the University of

St. Francis, and we have lengthy discussions on capital punishment. I have also

written many articles on the subject, but I would like to have you talk with me

about your feelings of the subject. However, I need you to give me a quick

thumbnail of who Rob Warden is, where he was born, grew up, and went to school. My interest in investigative reporting had caused

me to gravitate toward the law and lawyers as sources. When the Chicago

Daily News folded in 1978, I worked very briefly for the Washington Post

and then had an opportunity to start the publication, Chicago Lawyer,

where I was the editor and published it for ten years. We were really the first

to start writing about the wrongful conviction problem. Others merely wrote it

off as something that was just a sort of an anomaly of a well-functioning

system. However, these few flaws affected thousands, maybe as many as 100,000

people in America who are imprisoned at any given time for crimes that they

didn't commit.

My interest in investigative reporting had caused

me to gravitate toward the law and lawyers as sources. When the Chicago

Daily News folded in 1978, I worked very briefly for the Washington Post

and then had an opportunity to start the publication, Chicago Lawyer,

where I was the editor and published it for ten years. We were really the first

to start writing about the wrongful conviction problem. Others merely wrote it

off as something that was just a sort of an anomaly of a well-functioning

system. However, these few flaws affected thousands, maybe as many as 100,000

people in America who are imprisoned at any given time for crimes that they

didn't commit.  Some even said, "This guy is probably not innocent,

but this is just one of those cases in which we can't meet our burden of proof

beyond a reasonable doubt. You know, this is the best system in the world, but

no system of course is perfect. Nevertheless, this guy is probably guilty as

charged. If he is innocent, boy that's terrible, but rest assured this would be

a very rare occurrence."

Some even said, "This guy is probably not innocent,

but this is just one of those cases in which we can't meet our burden of proof

beyond a reasonable doubt. You know, this is the best system in the world, but

no system of course is perfect. Nevertheless, this guy is probably guilty as

charged. If he is innocent, boy that's terrible, but rest assured this would be

a very rare occurrence." The other phenomenon is that they arrest some kid,

the kid is in the county jail, and he has been there for six months awaiting

trial. The prosecutors say, "Look if you plead, we will recommend a one year

sentence. You can basically walk out the door; here is the key to your cell."

If the kid says that he is innocent, then they say, "Well, if you are found

guilty, then you will have to do for five years. Do you want that or do you

want to take our deal here?" That is the insidious plea bargaining dilemma. It

is really a modern form of torture. Usually, if you want to get a handle on the

problems that we have in society, we just set our social scientists loose to go

out and do a survey. For example, do you want to know how much unreported rape

there is? We go out and survey women. "Have you ever been raped? Did you

report it to the police?" Then we publish the results. We can't go into a

prison and say, "Hey, how many of you guys are innocent?" There is no way to

prove the percentage of innocent. We have to look for other means rather than

conventional social science techniques to get a handle on how serious this

problem is. Whether it is 5%, 10%, or even 1%, it's still a serious problem.

The other phenomenon is that they arrest some kid,

the kid is in the county jail, and he has been there for six months awaiting

trial. The prosecutors say, "Look if you plead, we will recommend a one year

sentence. You can basically walk out the door; here is the key to your cell."

If the kid says that he is innocent, then they say, "Well, if you are found

guilty, then you will have to do for five years. Do you want that or do you

want to take our deal here?" That is the insidious plea bargaining dilemma. It

is really a modern form of torture. Usually, if you want to get a handle on the

problems that we have in society, we just set our social scientists loose to go

out and do a survey. For example, do you want to know how much unreported rape

there is? We go out and survey women. "Have you ever been raped? Did you

report it to the police?" Then we publish the results. We can't go into a

prison and say, "Hey, how many of you guys are innocent?" There is no way to

prove the percentage of innocent. We have to look for other means rather than

conventional social science techniques to get a handle on how serious this

problem is. Whether it is 5%, 10%, or even 1%, it's still a serious problem.

Al: Whatever the percentage is, how would you break

it down?

Al: Whatever the percentage is, how would you break

it down? Al: Why would someone confess to a crime that he didn't commit?

Al: Why would someone confess to a crime that he didn't commit?

A very good example would be the case of Gary

Gauger in McHenry County, Illinois. Gary was convicted and sentenced to death

for the murder of his parents, a crime for which the prosecution contended he

confessed. Gary always denied that he confessed or intended to confess, but the

circumstances were that he wakes up in the morning and finds his father

apparently dead. He calls 911, they come and soon find his mother dead. Gary

is the only person around and naturally is a suspect. They take him in for

questioning, and after twenty-seven hours of interrogation, they claim that Gary

confessed. Now, Gary's story is somewhat different. He says that the police

told him that they found bloody clothes and a knife in his room, and that he had

to have done it. He must have done it somehow and then blacked out, and that's

why he doesn't remember it. After twenty-seven hours, Gary starts thinking that

the police must be correct. Maybe, he blacked out and doesn't remember it. The

police tell me that it is a common phenomena, somebody does something like this,

in the midst of momentary insanity and blackout. Then they tell Gary just start

hypothesizing about how you might have done it. How would he do it if he had

murdered his parents? Maybe thinking about it would jar your memory, and it

will all come back to him. Gary finally starts thinking he did it. Then there

was a jailhouse snitch who claimed that Gary confessed the whole thing. That's

the evidence that convicted and sent Gary Gaugher to death row.

A very good example would be the case of Gary

Gauger in McHenry County, Illinois. Gary was convicted and sentenced to death

for the murder of his parents, a crime for which the prosecution contended he

confessed. Gary always denied that he confessed or intended to confess, but the

circumstances were that he wakes up in the morning and finds his father

apparently dead. He calls 911, they come and soon find his mother dead. Gary

is the only person around and naturally is a suspect. They take him in for

questioning, and after twenty-seven hours of interrogation, they claim that Gary

confessed. Now, Gary's story is somewhat different. He says that the police

told him that they found bloody clothes and a knife in his room, and that he had

to have done it. He must have done it somehow and then blacked out, and that's

why he doesn't remember it. After twenty-seven hours, Gary starts thinking that

the police must be correct. Maybe, he blacked out and doesn't remember it. The

police tell me that it is a common phenomena, somebody does something like this,

in the midst of momentary insanity and blackout. Then they tell Gary just start

hypothesizing about how you might have done it. How would he do it if he had

murdered his parents? Maybe thinking about it would jar your memory, and it

will all come back to him. Gary finally starts thinking he did it. Then there

was a jailhouse snitch who claimed that Gary confessed the whole thing. That's

the evidence that convicted and sent Gary Gaugher to death row. The very first wrongful conviction that I ever saw

was in the early 80s. It was on the south side

of Chicago and involved a young

man named Lavell Bert. You can read about him on our website. Lavell had just

been convicted of a murder of a child. This happened near what was then Comiskey Park. A child is standing in the front door of his home and he is shot

dead. Lavell Bert confessed to this crime. The story that he told is quite

persuasive. He was intimidated by some rival gang members. So, he went home to

get a gun to protect himself. When he saw the rival gang members running down

the street, he fired a shot at them and missed. He did hit this child standing

in a doorway. He then ran down the street and threw the gun away. Of course,

they never found the gun, for good reason. However, Lavell confesses and is

convicted. Very shortly after the conviction, the grandmother of the victim

calls the judge and says, "Your honor, I think there has been a terrible

mistake. I found the weapon that I believe killed my grandson, and it was in my

daughter's bureau drawer. She has admitted to me that this was an accidental

shooting, and that she made up this story because she didn't want to admit what

had happened. She never thought that anybody was going to be charged and

convicted. She has now told me the whole story."

The very first wrongful conviction that I ever saw

was in the early 80s. It was on the south side

of Chicago and involved a young

man named Lavell Bert. You can read about him on our website. Lavell had just

been convicted of a murder of a child. This happened near what was then Comiskey Park. A child is standing in the front door of his home and he is shot

dead. Lavell Bert confessed to this crime. The story that he told is quite

persuasive. He was intimidated by some rival gang members. So, he went home to

get a gun to protect himself. When he saw the rival gang members running down

the street, he fired a shot at them and missed. He did hit this child standing

in a doorway. He then ran down the street and threw the gun away. Of course,

they never found the gun, for good reason. However, Lavell confesses and is

convicted. Very shortly after the conviction, the grandmother of the victim

calls the judge and says, "Your honor, I think there has been a terrible

mistake. I found the weapon that I believe killed my grandson, and it was in my

daughter's bureau drawer. She has admitted to me that this was an accidental

shooting, and that she made up this story because she didn't want to admit what

had happened. She never thought that anybody was going to be charged and

convicted. She has now told me the whole story."  In the case of Aaron Patterson, he had been

tortured and finally agreed to confess. However, with a paper clip he found in

the interrogation room, he carved into the bench he was sitting on, "I have been

tortured to confess." Then they brought in the State's Attorney to take the

confession that they have gotten him to agree to make, and he refuses. There

was simply no more reason to believe that he did it, than to believe that anyone

of a half a million other people in the area could have committed this crime.

There was no reason whatsoever. They convicted and sentenced him to death based

on a fabricated confession, a torture confession.

In the case of Aaron Patterson, he had been

tortured and finally agreed to confess. However, with a paper clip he found in

the interrogation room, he carved into the bench he was sitting on, "I have been

tortured to confess." Then they brought in the State's Attorney to take the

confession that they have gotten him to agree to make, and he refuses. There

was simply no more reason to believe that he did it, than to believe that anyone

of a half a million other people in the area could have committed this crime.

There was no reason whatsoever. They convicted and sentenced him to death based

on a fabricated confession, a torture confession.  Al: How was it that George Ryan imposed a moratorium

of the death penalty?

Al: How was it that George Ryan imposed a moratorium

of the death penalty?  Al: When I interviewed Sen. Paul Simon, we also

talked about capital punishment. He asked me, "Do you feel safer driving

through Illinois or Texas? One doesn't have the death penalty and the does. If

capital punishment is a deterrent, then you would feel safer in Texas."

Al: When I interviewed Sen. Paul Simon, we also

talked about capital punishment. He asked me, "Do you feel safer driving

through Illinois or Texas? One doesn't have the death penalty and the does. If

capital punishment is a deterrent, then you would feel safer in Texas." Al: Even Turkey wants to get in the EU and will have

to abandoned the death penalty?

Al: Even Turkey wants to get in the EU and will have

to abandoned the death penalty? You have to study it, understand it, and see that

there is no benefit to the death penalty. In addition, there are grave risks

involved in it. That's why we ought to abolish it. Most people simply haven't

gone into the issue in this depth. I think American politics tend to discourage

courageous leadership. Our leaders follow the polls. Mr. Dewey said, "Even the

Supreme Court follows the election returns." Well, the election returns are

largely based on uninformed opinion in many issues. That's the situation here

in the States, but it isn't that way in Europe.

You have to study it, understand it, and see that

there is no benefit to the death penalty. In addition, there are grave risks

involved in it. That's why we ought to abolish it. Most people simply haven't

gone into the issue in this depth. I think American politics tend to discourage

courageous leadership. Our leaders follow the polls. Mr. Dewey said, "Even the

Supreme Court follows the election returns." Well, the election returns are

largely based on uninformed opinion in many issues. That's the situation here

in the States, but it isn't that way in Europe. Al: I have really enjoyed this interview; you have

made a lot of sense.

Al: I have really enjoyed this interview; you have

made a lot of sense.